Despite a weakening economy with deflation risks and disappointing corporate profits, China’s stock index has climbed. Analysts and investors are divided on the sustainability of this market trend. Lianhe Zaobao senior correspondent Chen Jing looks into the matter.

On 3 September, while most Chinese were glued to their TVs watching the country’s military parade showcasing its cutting-edge weaponry, a WeChat group of stock investors in Shanghai was more focused on the falling stock index instead.

At 11 am, someone asked: “The military parade’s over — why hasn’t the market rebounded yet?”

Another likened themselves to garlic chives — constantly cut down only to regrow and be exploited again: “Looks like we ‘garlic chives’ are the ones paying for today’s parade!”

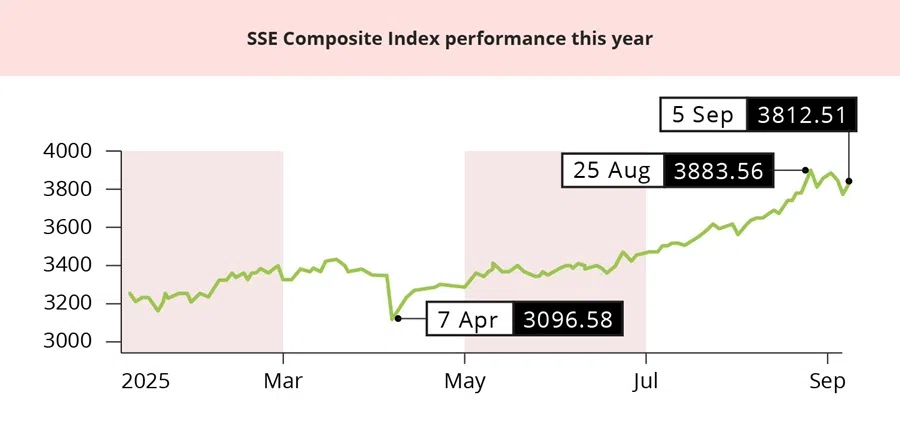

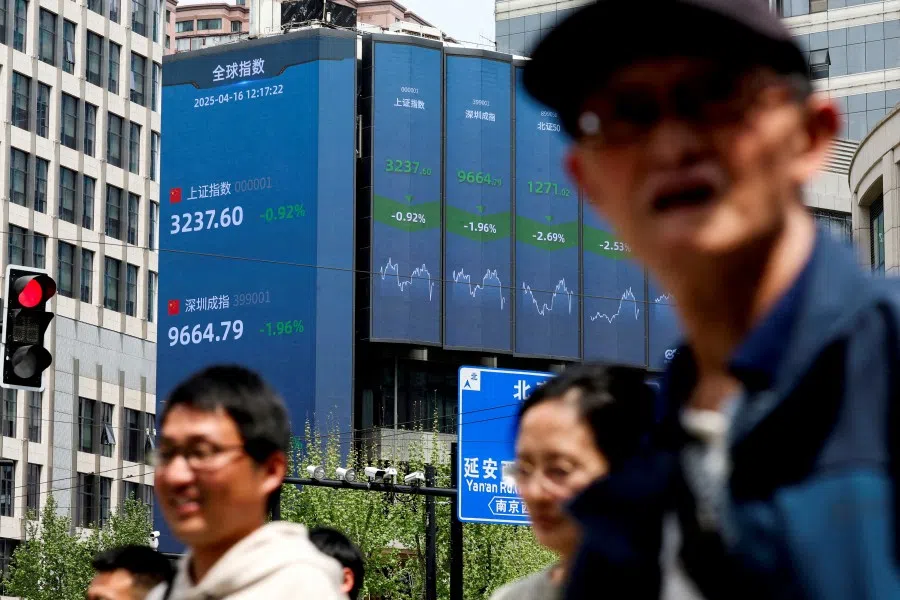

That day, the benchmark Shanghai Composite Index fell 1.16% to 3,813.56, marking its second consecutive decline. By 5 September, the index had edged back up 1.24% to 3,812.51, but still ended the week down 1.18%. [NB: China stocks edged higher on 12 September, with the Shanghai Composite hitting a decade-high of 3892.73 — its highest since August 2015.]

As Chinese investors hope for new market highs, some financial institutions started sensing danger.

Previously, the Shanghai Composite Index had hit a decade high of 3,883.56 on 25 August, just shy of the symbolic 4,000-point mark. The CSI 300 Index — the blue-chip index for mainland China stock exchanges tracking both the Shanghai and the Shenzhen markets — had risen nearly 17% since the start of the year, not only reversing a three-year downtrend but also outperforming major indices in the US, Europe and Japan.

However, entering September, A-shares showed signs of retreat, bringing a longstanding debate back into focus: is this four-month rally the start of a “slow bull” market or the prelude to a bursting bubble?

Disconnected from reality?

After the outbreak of the China-US tariff war in April this year, A-shares fell to a low of around 3,000 points before steadily recovering. Since July, the market accelerated its climb, with the Shanghai Composite Index successively breaking through 3,600, 3,700 and 3,800 points, while daily trading volumes hit record highs in August.

As Chinese investors hope for new market highs, some financial institutions started sensing danger. In late August, HSBC analysts warned in a report that the rebound felt disconnected from reality.

A series of data released last month showed that the Chinese economy has yet to be rid of deflation risks. The consumer price index was flat year-on-year in July, the producer price index recorded 34 consecutive months of decline, new RMB loans fell for the first time in 20 years, property sales accelerated their drop, and growth in fixed-asset investment, value-added industrial output and retail sales all slowed across the board.

With macroeconomic data underperforming expectations, corporate profits also disappointed. As of 30 August, nearly 23% of A-share companies that reported half-year results recorded losses — the highest level in almost a decade.

With poor returns from bank deposits, bonds and property, the stock market has become increasingly attractive to investors.

Capital driven into stock market

With no clear improvement in fundamentals, why has the stock index continued to climb? Analysts attribute the current rally to capital shifting from the bond market to the stock market, driven by China’s low-yield environment, which has boosted market liquidity.

Since 2023, the People’s Bank of China has repeatedly cut interest rates and reserve requirement ratios, pushing down bank deposit rates and bond market returns. The yield on ten-year government bonds has fallen from around 2.8% at the start of 2023 to approximately 1.76% now. Meanwhile, expected returns on bond-focused wealth management products have dropped from about 5% in early 2022 to around 2% this year.

Moreover, the once-preferred investment avenue of Chinese households — real estate — has slumped, further narrowing their options. With poor returns from bank deposits, bonds and property, the stock market has become increasingly attractive to investors.

The China International Capital Corporation Limited noted that in July, non-bank deposits rose by 1.4 trillion RMB (roughly US$196 billion) year-on-year, while the growth of bank wealth management products was 900 billion RMB less than the previous year. This divergence suggests that funds flowing into stock accounts may be a key driver of the increase in non-bank deposits.

Besides retail investors, insurance companies are also pouring into the stock market. According to investment bank Jefferies, in the first half of this year, Chinese insurers invested 620 billion RMB in stocks and funds, nearly matching the full-year total of 630 billion RMB in 2024. While much of this was allocated to high-dividend Hong Kong stocks, such southbound flows have slowed since June. In other words, more capital is now heading into A-shares.

“Although lacking the support of fundamentals, as long as there are no major shocks to the Chinese economy in the near term, the current uptrend could continue for a while.” — Shen Meng, Director, Chanson & Co

Foreign capital also jumping on bandwagon

Even foreign capital — often seen as “smart money” — is joining in. According to data from Geshang Wealth, around late August, active foreign capital recorded its first net inflow into A-shares since October last year, with inflows accelerating between 25 and 29 August. A Goldman Sachs report also noted that China has become the top market for net buying in global hedge funds in August, with hedge funds purchasing A-shares at their fastest pace in nearly two months.

Shen Meng, director of Chanson & Co, told Lianhe Zaobao that improved sentiment driven by diversified capital inflows has fuelled the rapid rise in A-shares, further attracting more investors into the market. “Although lacking the support of fundamentals, as long as there are no major shocks to the Chinese economy in the near term, the current uptrend could continue for a while,” he said.

Analysts are divided on how much longer this rally can last.

Goldman Sachs’ chief China stock strategist Liu Jingjin and his team have raised their target price for the CSI 300 Index, suggesting there may still be around 10% upside over the next year. They argue that China’s stock market valuation remains attractive, and earnings of major indices will maintain a high single-digit growth up to next year, and that investor positioning is not yet crowded, leaving room for further growth.

Morgan Stanley, however, has warned that A-shares are beginning to show scattered signs of overheating. While not yet widespread, the firm stressed that continued gains will depend on quick improvements in corporate fundamentals and stronger policy support.

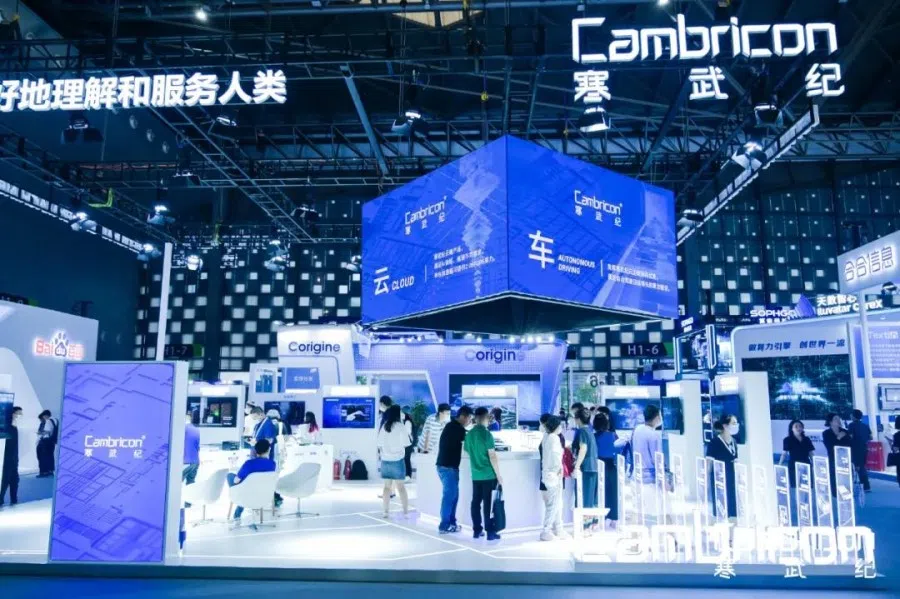

One sign of overheating is the overvaluation of certain stocks. Take the new “king of stocks” Cambricon Technologies. In just one month since 28 July, the AI chip design firm’s share price has surged 134%, closing at 1,587.91 RMB on 28 August, surpassing former “stock king” Kweichow Moutai. At that point, Cambricon’s rolling price-to-earnings ratio reached a staggering 5,117.75 times, far above the industry average of 88.97 times.

That evening, Cambricon issued a statement warning that its stock price risked deviating from fundamentals, and that investors could face significant risks. Its share price then fell sharply, and by Friday’s close had retreated nearly 20% from its high, down to 1,281.46 RMB. Cambricon rebounded past 1,500 RMB on 12 September.

… if the US Federal Reserve cuts interest rates as expected — or more aggressively — next week, A-shares would most likely rally alongside other markets. The upcoming Chinese National Day holiday could also sustain optimism and push the market higher.

Meanwhile, a rapid rise in margin financing and securities lending has also fuelled concerns of a bubble. Data show that on 1 September, outstanding margin financing hit 2.3 trillion RMB, surpassing the 2015 peak.

Chanson & Co’s Shen Meng noted that if the US Federal Reserve cuts interest rates as expected — or more aggressively — next week, A-shares would most likely rally alongside other markets. The upcoming Chinese National Day holiday could also sustain optimism and push the market higher. “But after the holiday and once the Fourth Plenary Session of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) concludes, with all expectations priced in, institutions may withdraw, triggering a sharp pullback in the indices,” Shen said.

Many investors still carry painful memories of the 2015 A-share roller coaster: back then, the Shanghai Composite Index soared 60% in just five and a half months to hit a record 5,178.19 points on 12 June, only to plunge soon after that, erasing all the year’s gains within three months.

On 4 September, Bloomberg quoted people familiar with the matter as saying that Chinese financial regulators, worried about retail investors suffering heavy losses from market volatility, are considering cooling speculation in A-shares, including lifting some short-selling restrictions and curbing speculative trades.

Building a US-style ‘slow bull’ market

At a special meeting in Beijing in late August, China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) chair Wu Qing stressed the need to consolidate the capital market’s stabilising momentum and to promote long-term, value and rational investing.

Commentators suggest that regulators should seize this period of ample liquidity to advance reforms, break free from the long-criticised boom-and-bust cycles, and create a “slow bull” market akin to US equities.

“These companies now find it harder to raise funds in the US. China must build a sound and stable domestic financial market in order to give them a good financing environment.” — Tan Kong Yam, Emeritus Economics Professor, Nanyang Technological University

Nanyang Technological University emeritus economics professor Tan Kong Yam noted that A-shares have long been dominated by retail investors, making them highly volatile and weakly connected to the real economy. While past reform efforts often stalled, growing internal and external pressures are now pushing policymakers to take the stock market more seriously.

Tan said that after the collapse of the property market, China urgently needs a new wealth engine. Meanwhile, with US-China competition intensifying, innovative tech firms are critical to winning the race. He added, “These companies now find it harder to raise funds in the US. China must build a sound and stable domestic financial market in order to give them a good financing environment.”

After the CCP’s Politburo meeting in September 2024 called for “efforts to boost the capital market”, the Politburo meeting in July this year again emphasised the need to “enhance the attractiveness and inclusiveness of domestic capital markets”. According to Galaxy Securities managing director Zhang Jun, this highlights the capital market’s elevated role in China’s national strategy: “Its importance has been raised to an unprecedented level.”

Wu Qing, dubbed the “broker butcher”, has also bolstered confidence in a new wave of reforms. Since taking office in February last year, he has led the CSRC in introducing structural reform measures: tightening IPO and delisting requirements, cracking down hard on financial fraud, guiding long-term capital such as insurance funds and pensions into the market, and encouraging listed companies to increase dividends.

Tan felt that if the aforesaid reform measures can be consistently advanced, coupled with global liquidity, there is hope that China can build a robust stock market that supports wealth accumulation, innovative financing and retirement security. However, if the political will to push reforms is insufficient and economic fundamentals are unable to support valuations, this bull market might just be the beginning of another cycle of boom and bust for A-shares.

He said, “We are observing not just a market story, but a shift in China’s political-economic strategy.”

… more than 2.65 million new A-share accounts were opened in August, a 35% increase from July and a 165% year-on-year increase.

Differing sentiments towards current bull market

In March this year, Wang Liang, a 30-year-old white-collared worker in Shanghai, quit his job and began investing more of his savings and energy into the stock market.

Wang told Lianhe Zaobao that he decided to dabble in stocks because of the current low bank interest rates. “I don’t have high expectations of the stock market, I simply ask that returns outperform bank deposit interest rates,” he said.

As bank savings rates continue declining, increasingly more Chinese citizens like Wang are shifting their savings from banks to the stock market. Massive household savings are becoming an important pool of funds boosting A-share liquidity.

Data from China’s central bank showed that the balance of household deposits within China reached a historical peak of 162 trillion RMB in the first half of 2025. JP Morgan forecast that from July 2025 to the end of 2026, about 2.5 trillion RMB of savings could flow into the A-shares, pushing stock prices up by more than 20%.

Strong upward momentum of A-shares over the past two months has driven more new investors into the market. According to data released by the Shanghai Stock Exchange on 2 September, more than 2.65 million new A-share accounts were opened in August, a 35% increase from July and a 165% year-on-year increase.

The surge of enthusiasm from retail investors entering the market prompted commercial banks such as Huaxia Bank and China Minsheng Bank to tighten credit card regulations, warning customers not to use credit card funds and cash advance functions for stock investment, or related transactions would be cancelled.

Wang is also a beneficiary of this bull market. His investments in co-packaged optics funds and semiconductor stocks have yielded a return of 25% so far this year — far exceeding his targets.

Seasoned investors left puzzled

While new investors embrace the bull market, some seasoned investors are left puzzled. Zhuang Yi, a retiree who has been trading stocks for 32 years, told Lianhe Zaobao that it took him quite a while to understand this round of market trends.

The 69-year-old entered the stock market as early as 1993. He recalls that back then, A-shares operated on a “T+0” mechanism, allowing multiple trades in a day, which fostered his habit of short-term trading. “I would buy a stock today and sell it in two or three days at most, and not hold on to it.”

During the turbulent market of 2015, when A-shares experienced rapid ups and downs, Zhuang was quick to sell his stocks before the market hit its limit down, making him one of the rare few retail investors who profited during the crash. However, he notes that this year’s market trends were noticeably different from those of ten years ago.

Zhuang commented, “During the bull market back then, all stocks would rise. Recently, the index has been climbing, but not every sector is going up. I only came to realise lately that this rise is mainly about value stocks. The government now advocates value investing and encourages investors to hold stocks long term.”

Since last year, the CSRC has been continuously guiding long-term funds such as insurance funds, social security funds and pension funds into the market, aiming to reduce market volatility by increasing the proportion of patient capital. This would create a “slow bull” market similar to the US stock market.

However, Zhang Yuheng (pseudonym), who switched from investing in A-shares to US stocks, felt that it is difficult for A-shares to establish a market mechanism as mature as the US stock market just within a few years.

“Our generation got ripped off by the stock market right after graduation, and we’re now trapped by the real estate market after buying a house — we don’t have any money or confidence left.” — Zhang Yuheng (pseudonym)

Trapped by stock and real estate markets

In 2020, Zhang began investing in A-shares shortly after entering the workforce. He recalled that the market was still performing quite well until March 2022. He said, “The next two months saw Shanghai in lockdown, and the stock market plummeted. Everyone was trapped. There was a brief rebound after the lockdown was lifted in June. I quickly liquidated my holdings and never touched A-shares again.”

After switching to US stocks, Zhang’s biggest impression is that US stocks were more open and transparent, with a higher degree of marketisation, and the rights of investors were better protected.

Although US stocks also fluctuate, Zhang could clearly identify the economic or policy reasons behind the volatility.

He added, “A-shares are often emotionally driven. If there is a rumour that a company’s performance is good even before it releases its financial report, everyone would buy in. Once the report is out and indeed shows good performance, the stock price would, on the contrary, start to fall — it’s completely counterintuitive.”

Zhang believes that those who dabble in A-shares now are either young people who have just entered the market, or older people with spare money. He said, “Our generation got ripped off by the stock market right after graduation, and we’re now trapped by the real estate market after buying a house — we don’t have any money or confidence left.”

![[Big read] When the market soars but the economy struggles: China’s stock puzzle [Big read] When the market soars but the economy struggles: China’s stock puzzle](https://todaysnews.center/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Big-read-When-the-market-soars-but-the-economy-struggles-768x512.jpeg)